Experimental Guidelines

Reaction Numbering

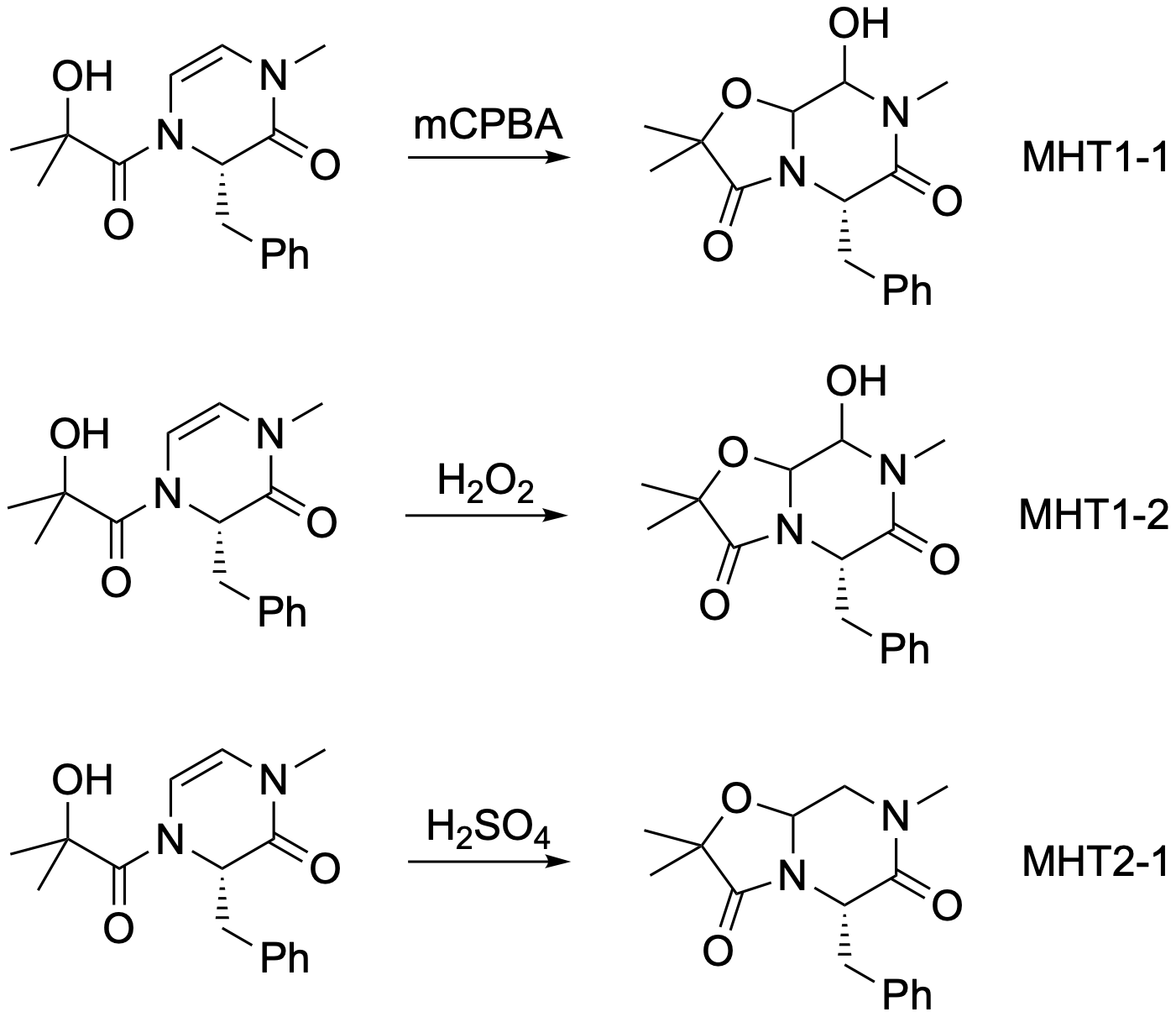

Reactions need to be given a unique identifier. The number takes the following form: YourInitialsX-Y where X is the reaction type and Y is the attempt number.

Reaction Type

A reaction type means ‘starting material-arrow-product.’ If you are attempting a certain transformation of a particular starting material to a particular product, then any attempt at this reaction has the same reaction number, regardless of reagents/conditions. The reaction has this number regardless of the outcome. It is the intention that counts. Stereochemistry of products is important – if the intended stereochemical outcome is different, the reaction has a different number. The numbering of reactions is unique to you; you do not use the same numbers as previous people in the group even if you are repeating their work.

Attempt Number

Attempt number just increases by 1 each time you do the reaction. Screening several different reaction conditions on small scale on the same page of your lab book can be named with ‘A’ ‘B’ ‘C’ after the full name if so desired, rather than exhaustively giving each reaction a different Y, so e.g. MHT1-2-3A, MHT1-2-3B etc. For reactions that produce multiple products, and where those products are isolated e.g. by column chromatography, additional numbers may be needed, MHT1-1-1, MHT1-1-2 etc, and the relevant spectra and vials should be labelled as such.

Example

The first three reactions in MHT’s lab book are shown below. The first reaction here is the first in the lab book. This transformation is given the number ‘1.’ It is the first attempt at this reaction, so it is called ‘MHT1-1.’ (ignore the third number - scheme needs fixing) The second reaction is the same transformation (remember, regardless of reagents), so also has X = 1. It is the second attempt so has the identifier MHT1-2. The third reaction is a different transformation, so has a different X, and this is the first time it has been done, so Y = 1, giving MHT2-1. Notice that there is no space between "MHT" and the first "1" - this helps with searching.

It is very useful to be able to find each example of each transformation, along with the yields. We used to have to keep tallies of this, but if you keep your ELN ordered and tidy, you should easily be able to find all the relevant attempts of a particular reaction.

ELN Write-Up

Accuracy

As a scientist, it is very important that you have a strong sense of when accuracy in measurement is needed and when it is meaningful. Consider three things in particular:

- The Sanity Check: Is what you're saying meaningful? Is the level of accuracy you are reporting really justified? Reporting concentrations of solutions used in work-up to three significant figures is clearly unnecessary, since nobody cares, e.g 0.5 N HCl is fine for a work-up, 0.507 N HCl is silly unless the solution is being used as a reagent. Never trust anyone who reports journal impact factors to three decimal places.

- Mismatch: Ensure measured and calculated accuracies match. If you weigh something to an accuracy of 3 significant figures, report the number of moles to the same level of accuracy (e.g. 1.30 mmol - not 1.304658 mol) since otherwise you're inventing precision - here the calculated value is more precise than you have measured, which is impossible. If Mat ever writes "accuracy mismatch" on your writing, he's talking about this, and you should check for other examples of this sin in your work.

- Consistency: Be consistent with accuracy. Thus within one preparation (but not necessarily within one report/thesis/paper) amounts should usually be reported with consistent accuracy. Typically this means reporting masses to three significant figures (e.g. 354 mg). Not doing this is a form of mismatch, since highly accurate measurements of one thing are made irrelevant by less accurate measurements of another thing. There are rare exceptions (like the concentration of work-up reagents, mentioned above, which do not impact the accuracy of your yield).

Transferring further information from old website in progess.

Relevant page on the old website can be found here in the meantime.

Sample Characterisation

If you want to make a molecule, the first thing to do is check whether it’s been made before. Use SciFinder frequently (often you'll need to use it daily). You can access previously-used methods, characterisation data etc. It’s the most important resource we have. Besides being able to search for literature examples of reactions you may be attempting, it's also a very rapid way to find characterisation data for compounds you're making (from the "experimental properties" link).

If you want to know how to handle a reagent, check e-EROS online.

When you use a starting material for the first time, acquire a 1H NMR spectrum of it to check its purity and to compare with your reaction product.

In general there are two kinds of characterisation required for molecules before we can publish the work:

For Known Compounds

These are compounds previously synthesised either in the group or by others in the chemical community. For these compounds we require three pieces of characterisation that match the literature (usually a 1H NMR, IR and low resolution mass spectrum). For crystalline solids we need a melting point and a comparison with the literature value, which can count as one of the three pieces of data. For enantiopure or scalemic compounds we require an optical rotation and a comparison with the literature value.

For Novel Compounds

For novel compounds, we require the full level of characterisation. This includes 1H and 13C NMR and IR spectra. We also need a low-resolution mass spectrum. For crystalline solids we require a melting point. If you have distilled a liquid, we require the boiling point. The ‘killer’ bit of characterisation that finishes off the data is either a high-resolution mass spectrum or (better) an elemental (CHN) analysis (not both). For enantiopure or scalemic compounds we require an optical rotation and some indication of the level of enantiopurity - this must come from chiral HPLC or NMR shift reagent analysis.

For any compounds that undergo some form of further evaluation (e.g. biological evaluation) we need some assessment of purity, which is usually gained from comparison of melting points (for known compounds) or analytical HPLC analysis (for novel compounds).

RF values are important for internal purposes, but have questionable reproducibility between labs. Thus while we need these values in lab books and internal reports, we do not generally report them in publications.

Spectra should be kept in order of their unique identifier in folders. The identifier and structure should be written clearly so that someone browsing the file can locate the appropriate spectrum quickly. Think about the people who will come after you. Generally if you're asked to produce a spectrum, you should be able to find it in a few seconds.

For NMR spectra, expand regions of interest - typically maybe 3-4 expansions for a 1H, one aromatic and one alkyl for a 13C. For writing up the data you will need the exact J values for each well-defined peak, and an accurate J needs ppm values for the relevant peaks to an accuracy greater than 2 decimal places. You must make sure the integrals for peaks have horizontal start and end lines, so that the values are real. Draw the structure of the molecule on the front page of the spectrum. Assign the peaks. If the spectrum shows a byproduct, draw this structure also. If the spectrum shows an unidentified product, draw the intended reaction and product on the front page, and indicate that the spectrum does not show this product. (It’s all about putting yourself in somebody else’s shoes and asking yourself whether your spectra would be clear to them – no mental notes)

For publication purposes, we almost always require scanned copies of 1H and 13C NMR spectra for the supporting information. Thus you must examine and assign spectra very carefully to ensure that there are no ‘rogue’ peaks and no large solvent peaks. Obtaining clean NMR spectra and assigning them is the most important skill of the synthetic chemist. Once you've done all the above with your spectrum, you can show it to Mat.

Experimental Write-Up (for papers/reports)

Transferring information from old website in progess.

Relevant page on the old website can be found here in the meantime.

Experimental Philosophy

Thin Layer Chromatography

This is the most useful assay for reaction completion you will ever use. There are lots of guides online about how best to do a TLC. Remember that the chamber the plate is in needs to be saturated with solvent vapour (so put a filter paper in there), and the baseline needs to be above the level of solvent. Always do TLCs with multiple lanes (starting materials, reaction mixture and co-spots). Your spots should be small, and ideally applied with glass spotters, not plastic ones (in case plasticisers leak out). The ideal Rf values for distinguishing spots from each other and for accuracy are between values of 0.1 and 0.5. Rf values above 0.7 are useless, since spots run into each other and the Rfs just aren't accurate (because of solvent evaporation from the top of the plate). To translate a TLC into a chromatographic separation, you want your desired spot to have an Rf of 0.3-0.4. If you can separate spots on a TLC by 0.1 you should be able to isolate those spots 100% pure by either a manual column or the Biotage, with no mixed fractions. With experience you’ll get this number down from 0.1 to 0.05. Use TLC before LCMS.

Mass Balance

Let’s say you install a sensor on either side of the Sydney Harbour Bridge. Over the course of an hour it counts 1000 cars entering the bridge. The sensor the other side counts 750 cars coming off. You'd worry, right? So if have a gram of reagents in a chemical reaction, and you're expecting a 100% yield of product of 800 mg, and you isolate, from your crude reaction mixture, 350 mg you should similarly worry. You should be wondering where the mass has gone. This is the mass balance. If you're asked how a chemical reaction went, the first thing to describe is the approximate mass balance. Until you have some sense of where the mass has all gone, you don't have a good sense of the reaction outcome. You should certainly not be throwing anything away until this is sorted out. Naturally there will be some loss (reactant byproducts into the aqueous etc) but you should not routinely be losing lots of mass.

What Else Did You Get?

Related to the crucial concept of mass balance is having a clear sense of what else has been formed in a reaction besides the product you want. If your product yield is below about 60% you will be asked (by me, by others, by your thesis examiners etc) "what else did you get?" You need to be able to say something about where the rest of the mass went, e.g. "two other products were also formed that accounted for the remaining mass balance, but I'm not sure what they are yet" or "45% of the starting material was also reclaimed." To not know this is to miss a crucial aspect of doing the experiment beyond making a molecule: Finding Out What Happened. If you don't know what else happened, it's quite hard to improve the reaction next time: it makes a big difference to what you do next time if there's starting material left vs. if all the starting material was converted to something else.